The Battle of the Bulge ran for 40 days and involved more than 1 million American, German, and British troops. A defining moment for the Glidermen, I thought it might be interesting to look at the first 15 days of the Battle, and see what was happening with units and vets we know, as the larger battle swirled around them. Here are the results…

12/16/44

“Soldiers of the Sixth Panzer Armee! The moment of Decision is upon us. The Fuhrer has placed us at the vital point. It is for us to breach the enemy front and push beyond the Meuse. Surprise is half the battle. In spite of terror bombings, the Home Front has supplied u with tanks, ammunition, and weapons. We will not let them down.” Oberstgruppenfuhrer Sepp Dietrich, commander, 6th Pz Armee[i]

“In the fog enshrouded early morning hours of December 16, 1944, Adolf Hitler had launched the greatest offensive of the war in the west since the spring of 1940. Thirty Divisions, a quarter of a million men, with thousands of artillery pieces, armor, and military vehicles swept through the Ardennes forest, a historic route of invasion. Their objective was to capture the port of Antwerp and split the Allied armies.” [ii]

“A report found on a dead German officer showed the 116th Panzer Division was planning to capture St. Vith today and Bastogne tomorrow. To make this attack, the Germans had massed three panzer divisions in the central part of Belgium. The Germans were out to secure two major towns in Belgium, and probably points beyond. With this new information, Middleton realized this must be more than a mere spoiling attack.”[iii]

“I would sacrifice a Division to hold Bastogne”, he thought grimly.[iv]

“…a half dozen men sat drinking coffee in a 99th Division mess tent while to cook, Tyger by name, mixed a batch of pancake batter. Shells began flying overhead. “Give ‘em hell, boys!” on G.I said. A shell landed 100 yards away. “That’s incoming mail” said Tyger in surprise. Then came an explosion overhead and Tyger leaped in the air. As others stared at the shrapnel holes in the tent, Tyger slowly, fastidiously withdrew his foot from the can of batter, and started stirring again.”[v]

“After an hour, the barrage stopped. There was a stunned silence, but only for a moment. Then at key points all along the front giant searchlights from the east stabbed through the morning fog. American frontline positions, battered and smoking, were lit up. GIs stared out, faces white in the deathly glow. This was their first terrifying, bewildering taste of the new Nazi fright weapon, “artificial moonlight”. Now ghostly white-sheeted forms came out of the haze toward them, advancing in a slow ominous walk twelve and fourteen abreast.”[vi]

[i] Battle of the Bulge, p. 68

[ii] Skyriders, p. 90

[iii] No Silent Night, p. 41

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Battle, p. 24

[vi] Ibid., p. 26

12/17/44

“To the south…. Dietrich’s left panzer spearhead had better luck. The heavily armored battlegroup of 1st SS Panzer Division, Kampfgruppe Peiper, had knifed through the Losheim Gap t Honsfeld and pressed on to Bullingen. There, in spite of American artillery fire and intervening fighter-bombers, the rampaging Germans seized 50,000 gallons of V Corps gasoline. After forcing captured American soldiers to refuel their panzers at gunpoint, Peiper’s tank force thrust deep behind U.S. lines ….”

“Near the Belgian village of Malmedy members of the SS battle group killed 84 unarmed U.S. soldiers.”

“Peiper was confident that they would reach the Meuse River the following day.”[i]

“Blacked-out vehicles of the 7th Armored Division were now rolling south towards the Ardennes. From tank to tank a rumor began spreading that the war in Europe was over, that they were going to the Pacific. The crews scrawled in chalk on the sides of their tanks “Pacific Bound.”

“The stream of reports from the front had swollen to a flood. They were still frantic and fragmentary, confusing and conflicting. Even so Courtney Hodges now realized he was in serious trouble. Clearly a number of wide, deep holes had been punched in his front. This could be a full scale offensive.”[ii]

“The 82d and 101st Airborne were alerted on the evening of the 17th…”[iii]

”On Sunday evening, December 17, there was suddenly called general staff meeting. Knowing something was afoot, I stayed up until Colonel Danahy returned to our quarters with the announcement, ‘Well Fred, you are going to be with us for a while.’ Then he explained that the Division had been assigned a mission and that I must be restricted to camp for two or three days until released. I knew that the Germans were attacking and suspected that the Division was being summoned to meet the thrust. I knew it might prove to be a dangerous step, but I said ‘How about going with you Colonel?’ ‘We’d be happy to have you’ Colonel Danahy replied….The next day began the most awesome ten days I might conceive in the widest of nightmares.”[iv]

“’All I know of the situation is that there has been a breakthrough and we have got to get up there’ Brigadier General Anthony McAuliffe announced to his staff and regimental commanders, pointing to a spot on the map near the Ardennes forest. Once again the Screaming Eagles would be going into combat, but this time they would ride into war on the back of trucks instead of leaping from planes. Their original orders were simple: Proceed to Werbomont and join up with VIII Corps to stop the German advance.”[v]

[i] Battle of the Bulge, p. 102

[ii] Battle, P. 54

[iii] Fighting With The Screaming Eagles, p. 159

[iv] The Battered Bastards of Bastogne, p. 20

[v] No Silent Night, p. 50

12/18/44

“On the right wing of Dietrich’s army, The 1st SS Panzer Division penetrated deep behind American lines. Kampfgruppe Peiper fought its way across the Ambleve River at Stavelot, crushing the resistance of the hodge podge of engineers, anti-tank guns and members of the 526th Infantry Battalion who had barricaded the approaches to the bridge. Peiper’s men did not even pause to secure the town and pressed along the highway west to the next bridge at Trois Ponts. But as the first German tank lunged for that crossing, the waiting 51st Engineer Combat Battalion detonated charges which sent it crashing into the Salm River.”[i]

“By the morning of December 18, more than fifty German columns were probing into the Ardennes from Echternach to Monschau. Some had gone only a mile; half had pierced as far as ten and twelve; and one had raced almost thirty.”[ii]

“Just outside of Mildren’s command post, a Tiger with a dozen grenadiers aboard approached. He waited till it had closed to fifty yards, then raked the deck with his sub-machine gun. Half of the grenadiers were knocked off; the rest jumped and fled to the rear. Morrow grabbed an M-1, attached a rifle grenade and fired at the oncoming Tiger. It passed him, and swerved around, looking for the gnat attacking it. Morrow ran up closer, and fired another grenade from 5 yards out. The Tiger swerved inti a ditch. As it tried to back up, Morrow took careful aim and fired again. This time the grenade hit the ammunition rack and the tank burst into flame. Tankers wearing black tams jumped out of escape hatches, their clothing ablaze.”[iii]

“A junior staff officer made radio contact with colonel Boos. ‘Sir, we’ve GOT to have TD’s. We’re being overrun by Jerry tanks!’ ‘How many tanks?’ Boos asked calmly. ‘And just how close are they to you?’ There was a roar. The house shook, plaster fell in hunks. ‘Well, colonel’, said the officer at the radio, ‘if I went up to the second floor, I could piss out the window and hit at least six!’”[iv]

“The door flew open with a loud bang that made me sit bolt upright in my bunk. Other combat-weary men came immediately awake. Sergeant Vetland came blustering and shouting into the room, not bothering to shut the door behind him. A cold, damp December wind blasted into our already miserable room, adding to the chill and discomfort. A chorus of angry voices demanded that someone “Close the goddamned door!”

“’Awright you guys, let’s hit it!’ He bellowed. ‘Come on, of and on, let’s hit it. Let’s go, hubba hubba, one time. Off your ass and on your feet, start packing your seaborne rolls, we’re moving out-now!’ [v]

“Everyone began to pack frantically. A number of men were on leave in Reims and had to be collected. One man, so drunk he could hardly stand up, could not believe the recall order. It was not until much later that he realized what was happening.”[vi]

“’I was CQ (charge of quarters) when I received a phone call to get everybody up and ready to move out and the officer repeated the order. I said ‘Yes Sir!’ and ran into the quarters shouting, ‘Everybody up! Everybody up! We’re moving out!’ I was deluged with a barrage of boots – mess kits – everything imaginable. I was lucky to get out of there alive.’”[vii]

“Transportation for the move did not become available until about 1600 hours that afternoon. Tightly packed aboard open-bodied ten-ton trucks, which had been rerouted from supply missions, the 327 and 401 rode into the night.[viii]

“One of the last units to depart Mourmelon was the 1/401st Glider Infantry. Its commander was a veteran officer named Lieutenant Colonel Ray C. Allen. Unlike the paratroopers in the 502nd, who were all volunteers, the soldiers of the 401st were glider riders, and some were even draftees. Sometimes, in the airborne world, the paratroopers tended to look down on the men who rode into combat in gliders. In reality, the action was as dangerous as jumping from the sky, if not more so.”[ix]

“We got as much ammo and gear as we could, and then loaded up in trucks for the drive north to Belgium. I was wearing my long underwear, on top of that, my dress uniform, and on top of that, my combat uniform. Extra socks in my pockets, knit cap, gloves, and I was still freezing.”[x]

“’I can’t tell you a goddamned thing about what we’ll be doing except at this time we’ll be in Corps reserve’ he said in a southern drawl. ‘That is what they tell me, but I don’t believe it. I know you’ve got men who can’t take any more of this shit, so I want you to single them out and leave them behind. Draw ammo and rations from the supply room. Remember, it’s winter. Take overcoats, overshoes, and extra blankets. We leave as soon as the trucks get here, so get cracking!’”[xi]

“Middleton informed McAuliffe that per 12th Army Group, his orders were changed. The Screaming Eagles would be redirected to Bastogne. General Bradley had concurred with Middleton when Middleton had called earlier, telling him that Bastogne could be important to holding up the German offense, and he needed a Division, pronto.”

“As McAuliffe peered over Middleton’s shoulder at the map, he knew he had to get the word to the rest of the 101st column and let them know that Bastogne was their destination. He chose an assembly area for his men in the fields around Mande St. Etienne, about three and a half miles to the west of Bastogne.”[xii]

“Although we did not know it then, Bastogne was out destination, though inadvertently. Actually we were supposed to defend Werbomont, 20 miles north of Bastogne, but we were re-routed to Bastogne while we were on the way. It was cold, rainy and foggy when we passed through the town…”[xiii]

“…the entire convoy, looking like a gigantic snake, was moving over the French roads, passing through battlefields like Verdun and Sedan on the way to Belgium. I leaned against the trailer’s side and looked out over the darkening land: my mind’s eye could see hordes of WWI troops rising from the trenches and charging in great masses through a lethal barrage of artillery and small arms fire toward the enemy. Their ghosts were restless.”[xiv]

“Fifty of us are crammed into the big truck with high sideboards, kind of like pigs being hauled to market. There is standing room only, with no cover over our heads. The weather is very cold, with low clouds overhead…..Orders are given to lock and load all weapons. This is not normal practice.”[xv]

[i] Battle of the Bulge, p. 109

[ii] Battle, p. 97

[iii] Battle, p. 98

[iv] Ibid., p. 99

[v] Seven Roads to Hell, p. 17

[vi] Skyriders, p. 91

[vii] Ibid. p. 24

[viii] Skyriders, p. 91

[ix] No Silent Night, p. 57

[x] Carmen Gisi, B/401, No Silent Night, p. 59

[xi] The Battered Bastards of Bastogne, p. 23

[xii] No Silent Night, p. 59-62

[xiii] Fighting With The Screaming Eagles, p. 163

[xiv] Seven Roads to Hell., p. 34

[xv] Glider Infantryman, p. 154

12/19/44

“December 19th, 1944 was one of the most dismal days of the last year of the war in Europe. Word from the Ardennes was of a frightful rate of German advance. The headline in the Parisian paper Le monde nervously told that the enemy was on the move over a front of fifty miles. The weather continued to be abysmal. Low clouds and mist clung to the wintry Ardennes hills; intervention by the Allied Air Force was still impossible.”[i]

“We have two kinds of weather, bad and worse.”[ii]

“But Eisenhower agreed that Patton should attack to relieve pressure on Bastogne. He turned to the Third Army commander with a serious question: ‘When can you start?’ ‘As soon as you are through with me, ‘Patton told him.”[iii]

“…headquarters worried about their loss of contact with Kampfgruppe Peiper. At mid-day, Genfldm Model called for ‘air reconnaissance to determine the location of the advance guard.’ Out of radio contact, and under orders to thrust rapidly ‘without concern for your flanks’ Peiper had managed to get his battle group trapped in the Ambleve River valley. Attacking west from La Gleize to cross the river near Lorce, the heavily armored force managed to take Stoumont three miles to the northwest, but an attempt to penetrate further to Targnon was checked by determined resistance from the U.S. 30th infantry Division, dwindling fuel supplies and anti-tank fire…”[iv]

“Just north of Bastogne, the advancing 2nd Panzer locked horns with the 10th Armored Division’s Team Desobry at Noville.”[v]

“The tragedy of the Schnee Eiffel was concluded. Eight thousand Americans – perhaps nine thousand, for the battle was too confused for accuracy – had been bagged. Next to Bataan, it was the greatest mass surrender of Americans in history.”[vi]

“It was now up to the 740th. Having no radio, he gave Lieutenant Powers a hand signal to take the lead with his five tanks. Powers pushed through the fog, almost immediately spotting a Panther 150 yards ahead at a curve in the road. His first shot hit the German’s gun mantlet and ricocheted down, killing the driver and bow gunner. The panther burst into flames. Powers slowly pushed on, having no idea what lay ahead. A second big tank loomed up. Before the German could fire, Powers sent a round into the Tiger’s front slop plate. The shell bounced off harmlessly. Powers’ gun jammed. Since the radios were useless, he hand signaled the tank destroyer behind to move in. The Tiger, jarred by Powers’ first shot, fired two wild rounds. Then the American tank destroyer’s big 90mm roared. The Tiger flamed.”[vii]

“The General then proceeded to designate the bivouac of each of the Division’s units. He placed the four infantry regiments so that Ewell’s 501st would be near the outskirts of Bastogne, Sink’s 506th in line behind it, Chappuis’ 502nd next in order of assembly, and Harper’s 327th the farthest westward in the Mande St. Etienne vicinity.”[viii]

“Following orders, we dismounted, one company at a time to form up in loose company formations along the roadside. It was about 4:00 a.m. As each truck emptied, its driver would move a little farther down the road, make a U-turn, and then head back the way we had come. Before our truck moved out I asked the driver where we were. ‘This is Champs’ he replied. ‘Bastogne is straight ahead about three miles.”[ix]

“Early on Tuesday morning, December 19, thousands of wind burned and frozen Screaming Eagles clambered over the sides of their trucks at a roadside west of Bastogne. The men complained and stamped their feet in the cold. They had traveled 107 miles in more than eight hours through freezing sleet and cold-icy rain. Many were in poor spirits, having been almost fully exposed while huddling in the back of their open-topped ‘cattle cars’. “[x]

“As the cold and nervous paratroopers of Ewell’s 501st heard the distant gunfire, they hikes up their pack straps, shouldered their weapons, and marched off through town to the east. With barely a pause, the 101st Airborne Division had just joined the battle for Bastogne.”[xi]

“Unfortunately, the Germans had struck the first deadly blow hours earlier. The reports that reached the 327th of gunfire and burning vehicles to the west were true. The 326th Medical Company’s field hospital had been set up northwest of Flamierge in an open field at the intersection of the Marche Road and the Barriere Hinck, nicknamed ‘Crossroads X’ by the GIs. “[xii]

“Company G moves into a small brick schoolhouse at Mande St. Etienne. There, Regensburg briefs us on the immediate situation. The enemy isn’t all that close, or so he says – forty miles or more. Earlier in the day, the parachute regiments arrived and headed toward and around the town of Bastogne.”[xiii]

“Captain Towns called me on the 300 radio set and I was soon on the way to the CP. I could see companies A and B moving out and knew they had been committed. The CP was in the garage of a small stone house off the road. Men from the headquarters platoon milled about as I pushed my way through. The other platoon leaders were there, gathered around Captain Towns. He had the only map of the area and pointed out the positions we would take in the defense line. He told us what he knew about the German drive, which was more serious than he had been led to believe at Mourmelon. We heard that the defense line held by the 28th and the 106th Infantry Divisions had been shattered by enemy spearheads headed in our direction. He said that German troops dressed in American uniforms had been captured and warned us to challenge everyone regardless of dress. ‘Make goddam sure before you let anyone in’, he said adamantly.”[xiv]

[i] Battle of the Bulge, p.131

[ii] Joel, tour guide at Bastogne Barracks, October 2018.

[iii] Battle of the Bulge, p. 132

[iv] Battle of the Bulge, p. 135

[v] Battle of the Bulge, p. 137

[vi] Battle, p. 133

[vii] Battle. P. 135

[viii] The Battered Bastards of Bastogne, p. 39

[ix] Seven Roads to Hell, p. 47

[x] No Silent Night, p. 73

[xi] No Silent Night, p. 74

[xii] No Silent Night, p. 81

[xiii] Glider Infantryman, p. 155

[xiv] Fighting with the Screaming Eagles, p. 163.

12/20/44

“A few miles north of ST. Vith, Bruce Clarke, while inspecting a front line unit, was captured on the morning of December 20. ‘I’m General Bruce Clark of CCB’ he kept saying. ‘Like hell’ said one of his captors, an American MP. ‘You’re one of Skorzeny’s men. We were told to watch for a Kraut posing as a one-star General.’ Clarke argued vehemently. The decisions of the next few hours could determine the battle of St. Vith. The MPs ignored his protests and locked him in a building. Only a Kraut would have insisted the Chicago Cubs were in the American League.”[i]

“Now almost totally out of gasoline, Peiper radioed for a Luftwaffe drop of fuel, not knowing how close he was to American petrol.”[ii]

“Bastogne was the storm center of the southern half of the battlefield that day. By 3:30 p.m., Noville, the village defending its northern approaches, had been completely abandoned and the American survivors of the bitter two-day battle were retreating in bad shape to Bastogne.”[iii]

“That was the situation when we, the men of A Company straggled in from the perimeter around Noville, gaunt, ragged, dirty, cordite-splotched, and hungry. Most of us old men had been virtually without sleep since our trip to Paris on 14 December. It was now the twentieth. We came in small groups, wary, watching, and listening for ‘incoming mail’, ready to hit the ground at the first hint of another barrage.”[iv]

The fate of Bastogne was being discussed at that moment, 4:00 p.m., twenty miles to the southwest at the VIII Corps’s new command post in Neufchateau. ‘There are three German Divisions in your area,’ Troy Middleton was telling Anthony McAuliffe. ‘And the 116th panzer is on its way. You’re going to have a rough time staying there.’ ‘Hell, ‘replied McAuliffe, ‘if we pull out now we’d be chewed to pieces.’ ‘Well I certainly want to hold Bastogne,’ said Middleton. ‘But in view of recent developments I’m not sure it can be done.’”

“’Good luck, Tony.’ Middleton smiled. ‘Now don’t get yourself surrounded.’ Soon McAuliffe’s jeep was rolling up the Neufchateau-Bastogne highway – the only road into Bastogne not controlled by the Germans. Within an hour he entered his command post in the Belgian Barracks. He had narrowly missed capture but didn’t know it. A few minutes after he’d used the Neufchateau highway, it was cut by the Germans. Bastogne was now completely surrounded.”[v]

“In the north, Dietrich’s only advancing column was fighting for its life. Kampfgruppe Peiper now knew it was completely surrounded in the scenic mountainous area near Stoumont. Fifteen miles to its rear the rest of the 1st SS Panzer Division was still unable to drive across the Ambleve River into Stavelot and bring up desperately needed fuel, food, and ammunition.”[vi]

“We took special precautions to keep our identity a secret, just as we had on our previous mission. We were ordered to remove or cover our shoulder patches with a scrap of cloth sewn over them. As we entered Bastogne itself, many of the civilians remaining in the city came into the streets saying “welcome 101st, we knew you were coming.”[vii]

“We just got to the edge of Marvie. We were told to dig in. No sooner did we dig in than we were ordered to move further south; the “G” Company took our positions. No sooner do we get situated in our new holes when the Sergeant comes along and orders ‘Kocurek – take three men and go out to the edge of those woods. We’ve got to protect the flank – one guy from each squad.’ 1st platoon was 300 yards to my right. They had a building and a barn. Between us were open fields. The grass had been cut so there was no concealment for anyone trying to sneak up on us between the two platoons.”[viii]

“After being told that his regiment was to be in reserve and that the enemy troops were still 40 miles away, it was a real shock to PFC Donald J Rich to be involved in a combined armor-infantry attack on Marvie when his regiment had just arrived and had not yet completed the job of digging in. He wrote: ’The bazooka section had not yet set up when someone yelled, ‘There comes a German tank!’ I grabbed my bazooka and told one man to come with me. We ran up the street and into a house. I told the man with me to take the bazooka and stay at the window. I went into the next room to watch and told him to wait till the tank went by and then fire at it. He must have stuck his head up before the tank went by because the tanker fired into the house and blew a hole about three or four feet in diameter. I went rolling across the floor. I jumped up to see how my buddy made out. He came staggering out of the room. I rushed him to the medics. I never knew if he had serious wounds or if he made it. I ran back to the house to retrieve the bazooka. It was bent, with the barrel opening sealed. Someone else got the tank further on.’”[ix]

“Company C held a very vulnerable sector of the defense line with the greatest gaps between it and the other companies. The 2d platoon held the westernmost roadblock in the division, dug in on the slope of a rise among some trees with rolling hills and patches of woods to the front. In its rear on slightly higher ground was a great stone house with outbuildings surrounding a sunken courtyard. Tremendous fir trees bordered this area, as they did along the main road running between Bastogne and Marche 18 miles or so to the northwest. A 37 mm anti-tank gun was set in the trees facing down the road, and a Sherman tank and two tank destroyers moved into the courtyard. The roadblock appeared strong enough to stop anything coming down the road.”[x]

[i] Battle, p. 155

[ii] Battle of the Bulge, p. 141

[iii] Battle, p. 162

[iv] Seven Roads to Hell, p. 112

[v] Battle, p. 163-4

[vi] Battle, p. 166

[vii] Seven Roads to Hell, p. 55

[viii] The Battered Bastards of Bastogne, p. 135

[ix] The Battered Bastards of Bastogne, p. 137

[x] Fighting with the Screaming Eagles, p. 164

12/21/44

“On the ground, the average German soldier was elated. Most could not have imagined that the German High Command already considered Wacht Am Rhein a failure. For, after a terrible summer and autumn, Germany was again on the offensive and spirits soared. ‘What glorious hours and days we are experiencing’ a German volksgrenadier wrote home, ‘always advancing and smashing everything. Victory was never so close as it is now.’”[i]

“Out of gasoline with its supply line cut at Stavelot, Kampfgruppe Peiper in Stoumont and La Gleize repulsed attacks from all sides by the 30th Infantry and 3rd Armored Division. At mid-day Peiper held a conference with his battalion commanders in the chateau of Froide Cour just east of Stoumont to discuss their increasingly desperate situation. It was decided that the village must be surrendered in order to hope to successfully defend against future attacks. By evening his troops and the battleground command post had been moved back to La Gleize where the situation remained grim as well; the tiny 50 house village was being swept by gusts of artillery fire.”[ii]

“Around noon, Dollinger in his 213 and SS-Untersturm-führer Georg Hantusch in his 221 opened fire on 15 US tanks coming from Roanne but scored no hit. The American tanks fired back and blew off the front third of Dollingers tank’s gun. Hantusch’s King Tiger got also severely hit and both tank crews had to bail out. Dollinger, suffering from a head wound, took cover in the cellar of the Werimont farm. 213 was abandoned at the Werimont Farm when Kampfgruppe Peiper withdrew from La Gleize on foot.[iii]

“…that same day Patton began his offensive from the south in the midst of a swirling snowstorm. The pistol-packing general’s objectives were ambitious: halt any further advance of the German Seventh Armee, rescue the encircled paratroopers in Bastogne and cut through to Houffalize and cut off the German spearhead. “[iv]

“The busiest man in the entire sector, the man marshaling the Third Army into its attack position, was George Patton. He was visiting every division and corps headquarters, warning commanders to rush into attack or be relieved. He was mingling with the enlisted men – one pearl handled revolver strapped outside his coat, another stuck in his waist – laughing, wisecracking. He drove his Army northward, dashing by jeep from place to place like a man possessed.”[v]

“Out beyond the western perimeter, Captain Robert McDonald and his Baker Company of the 401st Glider Infantry continued to discourage any moves by the enemy to push closer to Bastogne from that direction. They were still out about three to four miles west of the positions of Able and Charley in the Mande St. Etienne part of the perimeter.”[vi]

“’At 0800 on the morning of the 21st, it was “B” Company’s turn to set an ambush. The prize included nine half-tracks pulling artillery pieces, plus other small vehicles. Also included in the prize were enemy dead, wounded, and captured Germans. Two other attacks were broken up at the road block that day. On the third counter-attack, one enemy tank was knocked out and one captured along with more prisoners. The company was ordered to move back three miles to the MLR. This was accomplished on our newly acquired transportation.’”[vii]

“After destroying the roadblock and killing all the Germans there, the 327 Glider Infantry patrol made a sweep toward the hospital area on their way back to Bastogne. They were guided to the area by the loud continuous blowing of stuck horns on the still burning trucks. As they approached the site the patrol spotted nearly a hundred of the Germans who had butchered the wounded in the hospital. The Germans, confident no Americans were in the area, stood around some of the burning vehicles talking loudly and laughing. The Company Commander quickly plotted an ambush. He ordered the bulk of the Company to move quietly by a roundabout way, and set up in front of the Germans. At a prearranged signal from the troopers who had gone ahead, the platoon that waited in place raced noisily forward, yelling and shooting at the surprised, panic-stricken Germans, who immediately took off running toward a nearby woods on the far side of a clearing. When they reached the center of the clearing, they were in a killing zone. Caught in a deadly crossfire, they didn’t have a chance. The glidermen took no prisoners.”[viii]

“Kokott could not believe what he was reading. Capture Bastogne? It was one thing to use his Division to surround the town, but to capture it seemed a stretch. Did Von Luttwitz know something he didn’t know? Perhaps the Corps intelligence sections estimated that the Americans holding Bastogne had sustained greater losses than previously thought and, as a result, their morale was suffering? Still Kokott thought, it was ludicrous to think that one division could defeat another division in a deliberate attack, especially when the enemy division was dug in and firmly emplaced in a major urban center. Military logic dictated that you needed at least a two-to-one advantage in combat power before you even contemplated tackling a foe who was in a prepared defense. All this and he faced and American armored combat command in addition to an elite Airborne Division – some of the toughest fighters the Amis had…”[ix]

“We made a big mistake when we left our winter gear back at the supply dump. In the early hours of December 21, the temperatures continue to plummet and the snow deepens. The temperature drops well below freezing, approaching zero Fahrenheit. I check the K Rations, and among the six of us we have about three days’ worth of food if we eat sparingly. At daybreak, snow is still falling. I can hear tanks moving near Remoifosse, which is about a mile south of us, but I can’t see them.”[x]

“All around I could hear the sounds of fighting, sometimes muffled, other times just over the next hill. The snow began covering the ground and quickly got deeper. Foxholes now became freezers and no amount of stamping around could get one’s feet warm. The cold had more serious effects too. The actions on our weapons froze, and all the lubrication had to be removed. Men who had foolishly discarded their overcoats and overshoes now suffered horribly. They spent a miserable night, wrapped in blankets, shelter halves, and sleeping bags, and still cold. I checked my squad several times during the night, mainly to keep warm.” [xi]

[i] Battle of the Bulge, p. 145

[ii] Battle of the Bulge, p. 156

[iii] December 44 Museum website

[iv] Battle of the Bulge, p. 163

[v] Battle, p. 168

[vi] The Battered Bastards of Bastogne, p. 167

[vii] The battered Bastards of Bastogne, p.167-8

[viii] Seven Roads to Hell, p. 115

[ix] No Silent Night, p. 94-5

[x] Glider Infantryman, p. 170

[xi] Fighting with the Screaming Eagles, p, 166-7

12/22/44

“On December 22nd, ‘Watch on the Rhine’ picked up its pace. The rate of speed would have been even faster but for two obstacles. Standing athwart the German flood tide were an island and a peninsula. The island was at Bastogne, seriously hindering the attack by forcing Manteuffel to detour above and below it. The peninsula was the new horseshoe defense being hastily thrown up hastily behind the fallen St. Vith. It was almost an island, for its escape corridor to the northwest was being dangerously narrowed every hour by a second wave of attacking German troops.”[i]

“”…the situation for Kampfgruppe Peiper had become desperate. Out of fuel, surrounded by two American divisions and under constant shelling, Peiper had abandoned Stoumont and moved two mile east to hold out in ‘The La Gleize Cauldron’.”[ii]

“Just north of Elsenborn ridge and only two miles west of Hitler’s favorite town of Monschau, three ragged, shivering German paratroopers were stumbling up a hill. They were Baron Von Der Heydte, his executive, and his orderly. The day before, the Baron had decided his situation was impossible. He had wounded, prisoners, and no food. There was only one thing to do – break through to the German lines. Before ordering the starved remnants of the Kampfgruppe to split into groups of three, he had written note in English to the man he mistakenly believed commanded the opposing force, Major General Maxwell Taylor: ‘We fought each other in Normandy near Carentan and from this time I know you as a chivalrous, gallant General. I am sending you back the prisoners I took. They fought gallantly too, and I cannot care for them. I am also sending you my wounded. I should greatly appreciate it if you would give them the medical treatment they need.’”[iii]

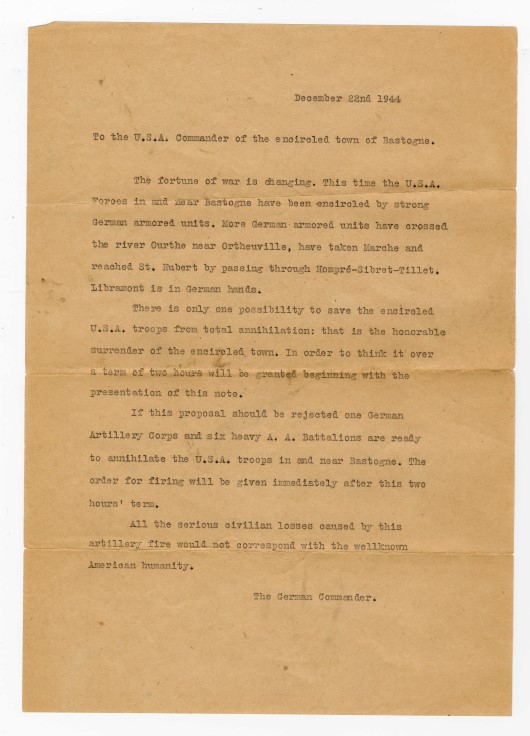

“Back at Bastogne, there had been ‘no change in the siege and encirclement front.’ Mindful of the mass capitulation of the American pocket in the Schnee Eiffel, the commander of the XLVII Panzer Corps, Gen. Von Luttwitz, took it upon himself to make a surrender request of the American bastion at Bastogne. ‘Along abut December 22nd I was having my greatest doubts, ‘Gen. McAuliffe remembered. ‘Many were wounded and supplies were short. Some guns were down to ten rounds each.’”[iv]

“…Major Alvin Jones, Colonel Joseph Harper’s S-3, took an incoming call from the 2/327th at Marvie. A trooper from Fox Company manning a roadblock had reported a bizarre sight: A group of four Germans – two officers and two enlisted men – carrying a white flag, had approached the 327th’s outposts near Remoifosse. The Germans had walked right up to the American foxholes on the Arlon Road leading straight south out of Bastogne.”[v]

“General A. C. McAuliffe had been up all the night before and was sacked out in deep sleep in his basement cubbyhole, next to the Division Command Post in the cellar. Colonel Moore went to General McAuliffe and shook him awake, saying ‘The Germans have sent some people forward to take our surrender.’ Still half asleep, the General muttered ‘Nuts!’ and started crawling out of his sleeping bag.”[vi]

“The Germans had allowed only two hours for an American response before they would resume their shelling and attacks. But when it came time to draft a reply, McAuliffe was at a loss for words. ‘That first remark of yours would be hard to beat’ Lt. Colonel Harry W. O. Kinnard, his G-3 told him. ‘What was that?’ McAuliffe asked. ‘You said ‘Nuts!’ Kinnard told him. The General’s staff voiced their approval. ‘That’s it!’ McAuliffe beamed. The irreverence of the response was perfect. It was so typically American, so oddball, so go-to-hell G.I.”[vii]

“As the blindfolds were removed, and the Germans were escorted to the main road, Harper spoke up once more. He wanted to make sure they understood the nature of the reply. ‘If you don’t understand what NUTS means’, he continued, ‘in plain English it means the same as ‘go to Hell’. And I will tell you something else: if you continue to attack, we will kill every goddamned German who tries to break into this city.”[viii]

“When word spread that they were surrounded, rivalry among the various units was suddenly forgotten. The paratroopers now grudgingly admitted that the 10th Armored Division teams had put up one hell of a fight and had saved the bacon during the first two days. The sharp rivalry among the regiments of the 101st also ceased. Of course, no self-respecting 501st man would want to be in the Five-Oh-Deuce, the 504th, or the 327th Glider. But those were pretty good outfits to have at your side. Negro artilleryman of the Long Tom outfit which had wandered into town were stuffing the bottoms of their trousers into their boots. ‘What the devil kind of uniform is that?’ a 101st officer asked curiously. ‘Man’, was the answer, ‘we’re airborne!’ So was their spirit.”[ix]

“” I was saved from the dilemma by the rumbling of a tank coming from second platoon. It stopped by me and a stocky sergeant got out. ‘Colonel Allen told me to run down the road and shoot up those houses’ he said in a quiet drawl. I pointed out the panzerfausts. ‘With those there? How far will you get? ‘What do you suggest then?’ I told him I was going to send a squad down each side of the road. If his tank could support them with his 75mm cannon and .50 caliber machine gun while Felker’s squad provided enfilading fire from the left flank, the plan might work. He agreed and I ran to Felker’s position to direct their fire. I gave a signal and all hell seemed to break loose. The tank cannon began its bark, its machine gun blazing. ‘A’ Company’s machine gun and riflemen added to the din and Felker’s men raked the German foxholes from the ide. The two attacking squads took off with yells, dodging from tree to tree along the road and firing at the foxholes in front of them. The Germans panicked as the 75mm blasted them out of houses and our enfilading fire kept them down in their holes. They hardly fired a shot in return. I was in an end slit trench with Felker. Our weapons were hot from firing clip after clip. The Germans around the shed and potato mounds had enough. They began to pull out. Only a few made it and soon their bodies littered the snow in bloody heaps. I hit one and he went down and began to scream. We brought him in later with a gaping wound from knee to hip. He was barely eighteen and scared to death. We dressed his wound and evacuated him to Bastogne with the other German wounded. The action ended, having taken about a half hour. Cries of ‘Kamerad! Kamerad!’ meant it was over. I went back to the tank on the main road. The tank sergeant was exuberant. ‘By God, I’ve been in this mess since D plus twelve and I’ve never seen anything like this. You’re a crazy gang’, he said.”[x]

“We set up our defenses, using captured MG-42s along with our won weapons. The tank went back to 2d platoon, the crew pleased with their contribution. If it hadn’t been for them, American bodies would have been lying alongside the Germans. Not long afterward, a jeep came down the road and stopped by the hamlet. General McAuliffe and some of his staff got out. He seemed to recognize me immediately as I saluted and told him about the action. He had complimented me in Holland when we were in positions along the Rhine. He did again, congratulating some of the men individually as well. His visit helped improve our morale and steady our nerves.”[xi]

“That night, the temperature plummets even lower. Ice forms, eighteen inches thick, along the sides of the foxhole. We can hear mechanized enemy troop movements to the south in the dark. At least we all have sleeping bags now, nut I am even more concerned about going to sleep and freezing to death. To keep awake, I stand in the sleeping bag all night long. We take turns keeping watch for the enemy. The wind is howling, and the foxhole still blocks the wind, but it also seems to act like a freezer…”[xii]

“…the German weather service reported a rapid build-up of high pressure approaching from the east. According to the forecasts, a sustained period of improved weather could be expected in one or two days.”[xiii]

“Patton was delighted. His critics had been confounded. The three divisions had moved one hundred miles over strange roads, under icy conditions, in less than forty-eight hours. As predicted, his attack was on schedule. Now he gave an even more startling prediction. ‘We’ll be in St. Vith,’ he said, ‘by December 26.’ The week before, Patton had ordered his chaplain to publish a prayer for good weather for hi Saar attack. ‘See if we can’t get God to work on our side.’ ‘Sir’, replied Chaplain O’Neill, ‘it’s going to take a pretty thick rug for that kind of praying.’ ‘I don’t care if it takes a flying carpet.’ ‘Yes, sir, replied O’Neill reluctantly. ‘But it usually isn’t customary among men of my profession to pray for clear weather to kill fellow men.’ ‘Chaplain, are you teaching me theology or are you the Chaplain of Third Army? I want a prayer.’….Now, as Patton’s III Corps headed north to bite into the great German offensive, the prayer was being passed out, even though Patton’s chief of staff, General Gay, had reminded him that it had been printed for an earlier attack. ‘Oh, the Lord won’t mind’ was Patton’s answer. ‘He knows we’re too busy right now killing Germans to print another prayer.”[xiv]

[i] Battle, p. 191

[ii] Battle of the Bulge, p. 166

[iii] Battle, p. 198

[iv] Battle of the Bulge, p. 166

[v] No Silent Night, p. 106

[vi] The Battered Bastards of Bastogne, p. 205

[vii] Battle of the Bulge, p. 175

[viii] Battle of the Bulge, p. 176

[ix] Battle, p. 209

[x] The Battered Bastards of Bastogne, p. 193-4

[xi] Fighting With the Screaming Eagles, p. 171

[xii] Glider Infantryman, p. 176

[xiii] Battle of the Bulge, p. 168

[xiv] Battle, p. 206-7

12/23/44

“The advance warning of the German meteorologists had been correct; on Saturday, December 23rd the weather made a dramatic change. The sun rose to reveal a bright frosty landscape under a clear blue sky. Within two hours, the air over the Ardennes was filled with swarms of Allied planes. For the first time in a week Allied air power was able to intervene in the German counteroffensive. Hitler’s luck had finally run out.”[i]

“When Patton looked out his window on the Boulevard Paul Eyschen and saw the sun he was jubilant. ‘Hot Dog!’ he said. “I guess I’ll have another 100,000 of those prayers printed. The Lord is on our side and we’ve got to keep him informed of what we need.’ He called for his deputy chief of staff, Colonel Harkins. ‘God damn, Paul, look at that weather! O’Neill sure did some potent praying. Get him up here, I want to pin a medal on him.’”[ii]

“In foxholes circling Bastogne the bright sun was bringing welcome warmth to the town’s cramped frozen defenders. They had never before been so glad to see dawn. It had been a night of misery. Their foxholes had become refrigerators. Awake all night, they had danced up and down to keep from freezing. A half dozen times they had taken off tight paratrooper’s boots to massage their numb feet. Now they were trying to thaw out not only themselves but their pieces. One man’s M-1 rifle wouldn’t work. Checking, he found the ejector frozen. He resorted to the old soldier’s solution: he urinated on the cold metal.”[iii]

“We were told that the 101st Airborne Division in Bastogne was surrounded and we didn’t know if they had been overrun by Germans. We were to parachute in and set up our equipment if we landed in friendly territory and prepare to guide resupply missions into Bastogne.”[iv]

“We set up our equipment (CRN’s) there and waited for the first sound of incoming aircraft. We didn’t dare turn on the sets until the last minute because the Germans would have ‘honed in’ on us and blasted us to bits. Shortly, the sound of approaching aircraft grew louder and louder so we turned on the CRN-4s. Even though the Germans started firing at us, the sight of the aerial armada distracted them and we suffered no casualties. The air drop was a great success and a Christmas present that the beleaguered troops at Bastogne wouldn’t forget for a long time.”[v]

“Kampfgruppe Peiper was still encircled and throwing back the unremitting attacks of the 30th and 3rd Armored Divisions, ‘for breakfast on December 23rd,’ remembered one of the German battlegroup, ‘we got a double helping of artillery and mortar fire.’”[vi]

“”Our attacks from the west and east bogged down today’ said Harrison. ‘But tomorrow I’m going to try one from the north.’ From these wooded hills his men could approach La Gleize without being seen. Their conversation was brief and loud, for two howitzers and a great 155mm cannon, dug in next to the chateau, were lobbing tons of high explosive into Peiper’s final stronghold at La Gleize. This one cannon was giving Peiper more grief than any other gun he’d run up against. His men were in an almost constant state of shock from its pounding. In addition, he was low on ammunition and out of fuel. The day before he had radioed: ‘Almost all out Hermann is gone. We have no Otto. It’s just a question of time before we’re completely destroyed. Can we break out?’””

“And lacking the forces for a full-blooded concentric attack, the 26th Volksgrenadiers elected to hit Bastogne from the northwest. Artillery and werfer fire commenced before daybreak as the Grenadiers wormed in closer to the paratrooper foxhole line. The initial rush took the Germans to the village of Flamierge, but a hard-fought counterattack managed to push them back out.”[vii]

“Gisi recalled the bouncy and bumpy ride as the glidermen rode into Flamierge on the back of the jeeps and armored cars, and a light tank. After the shelling lifted, Rudolph Voboril’s jeep stopped just outside the town. With a wave of his hand, Voboril motioned two machine gun teams to set up and start spraying the edge of town like Chicago gangsters. Rd tracers spit out and lanced into the sky above the village.”[viii]

“Suddenly, the world seemed to explode in my face. I felt myself being tossed aside as if a giant bubble had violently burst at my feet. My ears rang, my vision blurred, my body felt as if it was on fire, and my nostrils filled with acrid smoke. A shell had dropped less than ten feet from us, bowling us over like pins in a bowling alley. All four of us were down. My chest was on fire and my arm numb. Gwyn lay in a crumpled heap, Wagner, Damato and I got up and limped closer to the wall of the house. Medics rushed outside and helped us to the temporary aid station. …I was lucky, my ammunition belt suspenders slowed up a chunk of shrapnel, which still buried itself just below the ribs on the right side of my chest. It was the size of a half dollar and the medics picked it out. But they couldn’t do anything with the piece in my right wrist, a jagged shard that had buried itself in the bones. The medics dressed our wounds, gave us shots of morphine and told us to lay on a pile of straw with the other wounded. For us the battle was over.”[ix]

“’Bob, I don’t think Wagner is coming back. I think we should make a break for it.’ I looked at the distance we would have to go and thought about his leg wound. He could hardly walk and I knew he could never make it. As for me, my wrist was extremely painful but the wound in my abdomen nothing to speak of and I knew I could move in a pinch…..The small arms and tank fore to the front petered out. Something told me we had been abandoned….The door was shoved in with a kick and a big German in a snowsuit came in, machine pistol leveled….’For you the war is over’. Sam spoke with him for a moment, then told us we were prisoners of war and would be treated as such.”[x]

“Ray Allen knew it was past time to go. All day he had listened to C Company’s desperate struggle to hold open the Mande corridor. By evening the bad news had arrived – the Germans had retaken the town of Flamierge. Voboril’s force had come back pell-mell, the same way they had gone out, riding on jeeps and greyhounds. This time, though, they brought wounded.”[xi]

“Despite this, the battalion managed to pull back to a new main line of resistance that was east of Mande St. Etienne and parallel to the Champs-Hemroulle road behind it. By 2200 hours that night, Allen informed Harper and McAuliffe that he had established his new command post near Hemroulle.”[xii]

“On the other side of the salient, the attack by the Panzer Lehr Division to capture Marvie could not get underway until nightfall after the American jabos buzzing through the Ardennes sky had gone home for the day. In spite of the strenuous efforts of the 901st Panzer Grenadier regiment the attack see-sawed through Marvie with each side in partial control of the village.”[xiii]

“The decimated platoon, led by 1lt. Tom Morrison of “G” Company, was dug in around a building on Hill 500, just to the south of Marvie. Morrison was about to be captured for the second time in four days. A platoon of Company C of the 326th Engineers led by 1lt. Harold Young would be forced to withdraw. Some of its members were captured. With that strong point taken out, the Germans approached “B” Company positions near the bridges with some of their tanks.”[xiv]

“The Germans want to take the town, which will make it easier for them to take Bastogne. The sounds of battle are intense. German tanks shell the American lines for about ten minutes. Because of the wooded areas between Marvie and me, I can’t see the action, and the sounds are muffled. Screaming enemy infantry and four tanks from two companies attack the platoon on Hill 500, splitting the American lines. The attackers are dressed in white snowsuits, making it hard to see them.”[xv]

“At the farmhouse where I am, the sounds of battle coming from the west are getting closer to me. First Platoon of F Company is being attacked on the Arlon Road as the sun goes down. Fighting erupts again to the east of me as second Platoon of Company F comes under attack. The enemy is on both sides of my position. Behind me, the woods are pounded by German artillery, with shells going over us and hitting behind.”[xvi]

“That night, more snow was falling – soft flakes at first, which became smaller and more like ice pellets as the dark of night spread into the pink stain of morning. The weather was uncomfortable for the exhausted men of the 1/401st, but in a way a blessing. The snow and fog would help to mask their movement as they continued to break contact and withdraw. The bulk of the men retreated almost two miles closer to Bastogne. As the drained glider fighters of C Company threw A6 machine guns, mortar plates, and ammo over their shoulders and quietly moved out, they took one last glance at Flamierge and Flamizoulle in the distance. The villages were largely quiet and, in the softly falling snow, resembled something from a peaceful Currier & Ives print. Allen’s men guessed by now that the twin towns were completely occupied by German soldiers……Regardless, Allen let all of his men know they could pull back no more. That night he told his men, ‘This is our last withdrawal. Live or Die – this is it.”[xvii]

[i] The Battle of the Bulge, p. 177

[ii] Battle, p. 219

[iii] Battle, p. 220-1

[iv] The Battered Bastards of Bastogne, p. 222

[v] The Battered Bastards of Bastogne, p. 225

[vi] The Battle of the Bulge, p. 178

[vii] The Battle of the Bulge, p. 180

[viii] No Silent Night, p. 122

[ix] Fighting With The Screaming Eagles, p. 195

[x] Fighting With The Screaming Eagles, p. 196-7

[xi] No Silent Night, p. 145

[xii] No Silent Night, p. 147

[xiii] The Battle of the Bulge, p. 180

[xiv] The Battered Bastards of Bastogne, p. 237

[xv] Glider Infantryman, p. 177

[xvi] Glider Infantryman, p. 178

[xvii] No Silent Night, p. 147

12/24/44

“In the pre-dawn darkness on December 24th, Christmas Eve, Peiper and his battlegroup were in the process of escaping from ‘the cauldron’ in La Gleize. Hopelessly surrounded and under continuous attack from all sides, Peiper and 800 men managed to slip out of their encirclement in the dark. The heavily armored battlegroup had been practically destroyed, being forced to leave behind countless dead, 400 wounded and almost all of the Division’s panzer regiment. “[i]

“”The allied air forces were committed to the Ardennes fighting in mass on Christmas Eve with over 5,000 sorties aimed at choking off Heeresgruppe B’s supplies and smashing the panzer spearheads. In fact, the 24th featured the greatest concentrated confrontation of air forces during the entire European war. Although the Luftwaffe managed 1,088 sorties, their largest air effort since D-Day, this ’could not produce the required relief.’ That day, the Seventh Armee bitterly reported not sighting a single German plane. Allied fighter-bombers buzzed over the battle area almost incessantly while bombers continued to pound railways and supply columns in rear areas. Later the same evening, Genmaj. Ludwig Heilman, in charge of the 5th Fallschirmjaeger Division, reported that: ‘At night, one could see from Bastogne back to the West Wall, a single torchlight procession of burning vehicles.’”[ii]

“Another air supply had come in that morning, right on cue, courtesy of more than 160 Troop Carrier C-47s. Besides ammunition, the Air Corps dropped several containers of K Rations. This time eleven of the flimsy CG-4 cargo-carrying gliders also came in, their spectacular landings in the snowy fields fascinating the GIs around Bastogne. Several skidded to a halt just outside artillery positions near Savy and Hemroulle. Like manna from heaven, the gliders were loaded with 1015mm and 75mm shells for big American guns.”[iii]

“Bastogne was outwardly peaceful on Christmas Eve, but by now the men in the surrounded town had given themselves a new title: the battered Bastards of the Bastion of Bastogne. At his command post, General McAuliffe was talking to General Middleton on the phone. The strain of the past week was evident on his face. ‘The finest Christmas present the 101st could get,’ he was saying somberly, ‘would be a relief tomorrow.’”[iv]

“McAuliffe’s basement headquarters had picked up a message relayed by VIII Corps from General Patton and the Third Army. Patton’s Third was still fighting their way north to the city, and now was only eight miles away. ‘Xmas Eve present coming up. Hold On.’ The message said. Like any good commander, McAuliffe wanted to nip any morale issues in the bud before it became problematic – especially on the holiday. Even if he was starting to have his own concerns, he wasn’t about to let on to any of his staff or soldiers. On the Christmas, he knew that many of the herd-pressed GIs would start to worry about home and family. It would be important to remind them why they were here. In a widely circulated flyer, Colonel Kinnard wrote the following Christmas message. McAuliffe approved it and had it distributed to all of the men in and out of frozen foxholes…”[v]

“The battle for Marvie petered out early Sunday morning, with the Americans holding half of the town, and the Germans the other. It certainly was not the conclusive key engagement Colonel Heinz Kokott had sought. He could tell by looking over the reports from the 901st Panzergrenadier Regiment, which had spearheaded the attack on Marvie. Once again the stubborn Ami paratroopers had refused to yield to common sense. Reluctantly, Kokott began to feel some admiration for his adversary, and he decided that everyone, including his higher headquarters, had underestimated he pluck of the GIs trapped in Bastogne. The attack on Marvie had foundered relatively early. Kokott knew by 2200 hours the previous night that the assault had become mired in the streets of the small Belgian hamlet. Indeed, the Operations center of the 901st reported to him at the time, ‘[T]he attack had been halted by increased enemy resistance and… there were no longer any reserves for continuance of the attack with any hope for success.’ Kokott knew it was senseless to continue reinforcing failure.”[vi]

“Earlier, Kokott had made a personal reconnaissance of the western roads to Bastogne. He was well aware of the strong resistance put up by the Americans near Mande St. Etienne and Flamierge. However, he was inspired when recon elements reported early morning retraction of the American lines in this sector. After four days of stubborn resistance, the Amis had finally pulled back their forces here. Perhaps, though Kokott, this was a clear indication that the Americans were stretched too thin in Bastogne’s western approaches.”[vii]

“Almost due west of Hemroulle the ground gradually climbed and flattened out into large, open fields. It was in this broad, snowy area before Allen’s headquarters that Town’s hard fought Charlie Company had entrenched some distance behind their brothers in Able and Baker companies….After the beating it had sustained the previous day, mercifully, Captain Towns’s Company was now in reserve. Shivering in their foxholes, some of the glidermen could hear the sound of gurgling panzer engines in the distance, coming from the direction of Salle and Tronle. For many, there was a sad resignation – they felt it was going to be their last day on earth.”[viii]

“The first reports of approaching German aircraft came over the radios around 1925 hours, and within minutes bombs were falling in the center of Bastogne. Adolf Hitler had unleashed his fury and frustration on the little Belgian town. Snarling, like fat mosquitoes, the bombers and the eruptions of their payloads – high explosive, fragmentation, incendiaries, and bright magnesium flares – blasted the still winter night.”

“What was once a building was now twisted, burning embers and smashed masonry…..’there were thirty two wounded men in there,’ a shocked lieutenant cried out, pointing at the monstrous, consuming inferno….The lieutenant then pointed at the debris and remarked, ‘One of the men told me that a Belgian nurse was caught under a falling timber just as she was nearly out,’ said the lieutenant. ‘She was taking care of the wounded.’”[ix]

“About midnight, I head over to the barn to warm myself with fresh milk. The Luftwaffe’s Bed Check Charlie is doing his thing, bombing Bastogne. The explosions ripple through the night air, and I can see flashed of fire. I can easily see the aircraft in the moonlight. Mesmerized by the sight, I leave the foxhole to get a better look. The plane looks like a Junkers fighter bomber. As the plane banks over Bastogne, heading toward my location, I can even make out the gunner in front of the aircraft, illuminated by lights inside. Closer the enemy aircraft comes. I think about shooting my rifle at the plane: I’ll just hit ol’ Bed Check Charlie. Then I hear a continuous whipping sound ahead of me. ‘What the…?’ I speak out loud as I glance down into the snowy landscape ahead of me. The snow is jumping up in the air in two columns coming my way. The aircraft gunner is shooting at me.”[x]

[i] Battle of the Bulge, p. 184

[ii] Battle of the Bulge, p. 187

[iii] No Silent Night, p. 161

[iv] Battle, p. 257

[v] No Silent Night, p. 162

[vi] No Silent Night, p. 158

[vii] No Silent Night, p. 157

[viii] No Silent Night, p. 171

[ix] No Silent Night, p. 180

[x] Glider Infantryman, p. 182-3

12/25/44

“On the morning of December 25th, 770 absolutely exhausted men of Kampfgruppe Peiper reached German lines along the Salm River near Rochelinval after suffering some casualties from repeated brushes with the 82d Airborne Division. With the capitulation of Kampfgruppe Peiper, the Germans along the Ambleve River were forced over to its southern bank.”[i]

“Patton was well aware of the American predicament in the isolated market town, but the Germans in the path of his 4th armored Division were putting up a brave if hopeless fight…..The Third Army Commander ordered the attack to be continued on through the night.”[ii]

“After another cold night, Christmas Day arrives without any special implications for me and my squad. …In the wee hours of Christmas, the enemy moves hard against the 401st and the 50nd to the west.”[iii]

“Reconnaissance of the area west of Bastogne had convinced Division that the next major attack along the perimeter would come from that direction and most likely it would come on Christmas day.”[iv]

“Perhaps the best measure of the fighting élan of this unit is that on the morning of the attack they were covering their ground with five .50 caliber machine guns and two light MG’s in excess of the two light guns allowed by the tables. They had scrounged this extra weapon power and were quite happy to carry it along.”[v]

“’The column of 60-ton German tanks began moving into Company A’s positions with their flame throwers blazing. Each tank had 15 or 16 infantrymen, wearing white sheets, riding on it and some infantrymen were walking behind the tanks. They were firing rifles and flame throwers as they came into 2nd Platoon’s positions The Germans were probing, trying to find my front-line positions. As soon as the last tank rolled through 2nd Platoon’s position, about 30 minutes later, the men of and platoon simply climbed out of 3rd Platoon’s positions and went back to their own positions, closing up the front line. No one told them to do it, they just did it and not one man failed to return to his position. Now they were behind the tanks and in front of the approaching infantry.

One of my men on the far left flank began firing a .50 cal. Machine gun, but no one else did any firing. This added to the deception. The German tanks thought they had just passed a weak outpost and kept on going. They didn’t know they had passed through a well-fortified front line position.

The TD’s were in the woods, 200 yards behind the CP and couldn’t see the German tanks until the tanks were right beside them. As the German tanks slowly rolled past them, one of the tank destroyer crews was cursed for ‘dallying’ by a German tank commander who though they were part of his force in the darkness and the heavy fog. No one answered him, no one fired, and they moved on. The German tanks slowly rumbled toward Company C. The tank crews thought they were well on their way to Bastogne. As soon as the tanks moved past them, the two tank destroyers pulled out of the trees and joined the other two tank destroyers on the left flank of the area. No one told the men to do it, they just did it. It’s important to point out that no one was giving orders at this time. You can’t tell someone what to do in a situation like this. The men were acting completely on their own.’

The only infantry troops accompanying the tanks were the ones riding on the backs of the white-washed tanks. Following five hundred yards to their rear cam the white-capped infantry troops. Colonel Allen continues: ‘They were still marching in formation in the field below the ridge. They were wearing white sheets, screaming and firing their rifles into the air. In the early pre-dawn light and the heavy fog, they looked like ghosts floating across the snow-covered field. They didn’t know they were just minutes away from their doom. They were heading into our well-hidden, machine gun final protective line on the ridge and my men were becoming angry as they watched hundreds of screaming German infantrymen coming toward them, but they stayed low, waiting for the Germans to get into range. Their plan was working. The German tanks were separated from the infantry and infantry still didn’t know where we were dug in. It was almost dawn and my men, four tank destroyers, our bazooka teams and Colonel Cooper’s 463rd Artillery team were all in position. Waiting – patiently, quietly waiting.

No one told them to wait. They knew if they made a mistake they were done for. The suddenly, the front line roared as my men began firing every gun they had and our machine gun final protective line went into full effect. The surprised German infantry was trapped in the flat, open field and were being cut to pieces by the cross fire from our machine guns.

The four tank destroyers had avoided a direct frontal fight with the tanks because of the thick armor plating on the front of the German tanks. When the first shot rang out, the tanks were still in a column moving toward my command post. Instantly, the four tank destroyers raced into position behind the tanks and opened fire. Five of the tanks exploded as their thin unprotected backsides took direct hits.

“C” Company was dug in and they were not going to budge one bit. Someone said they shot at anything and everything that could be German. Colonel Cooper’s 463rd artillery was so close to the tanks they had to level their muzzles and shoot almost straight across the ground to hit them. They fired point blank and said it was like ‘shooting fish in a barrel’. Now the tank column was being bombarded by fire from every direction. The column was surely staggered. Then, to escape the furious fire that was pounding them, it split up. Some of the tanks started racing toward Champs, two miles north, and six of them sped toward my CP in Hemroulle, two miles west of Bastogne.

My CP was beside the road from Champs to Hemroulle and on into Bastogne. It was about 7:15 a.m. now and Captain Preston Towns, the commander of Company C, called to warn me about the tanks speeding toward my CP. I asked him where they were and he said ‘If you look out your back window now, you’ll be looking right down the muzzle of an 88.’”[vi]

“When he peered out of the farmhouse, Allen learned that Towns was not exaggerating. An approaching panzer fired its main gun at the building. As Allen and his staff hugged the floor, the shell splintered the roof and passed through the structure, setting it afire….grabbing a radio, he quickly contacted Colonel Harper to let him know the battalion HQ was displacing and that the Germans had penetrated the American lines. When asked how close the German tanks were to his farmhouse, Allen responded ‘Right here! They are firing point blank at me from 150 yards range. My units are still in position, but I’ve got to run.’ When there was a break in the firing, Allen told the last two men remaining, Captain James Pounders and Captain Joseph S. Brewster, to ‘come on’. He grabbed an armful of papers, threw a piece of white parachute silk over his shoulders for camouflage, and bolted out the door just as a German tank picked him up in its sights. ‘The book says the tank was leading me with its fire, giving me credit for more speed than I possessed’, Allen later recounted with grim humor in an interview years later. ‘But I met an officer later who had just topped a hill when the tank started firing, and he saw the whole thing. I asked him if it was true the gun was leading me. He said ‘No, you were definitely leading it.’”[vii]

[i] The Battle of the Bulge, p. 197

[ii] The Battle of the Bulge, p. 197

[iii] Gilder Infantryman, p. 183

[iv] The Battered Bastards of Bastogne, p. 265

[v] The Battered Bastards of Bastogne, p. 265

[vi] The Battered Bastards of Bastogne, pp. 265-270

[vii] No Silent Night, pp. 247-9

12/26/44

“The five of us settle back into our foxholes. For our squad, Christmas dinner consists of more warm milk in the barn and K rations. In the late morning a messenger drops off a piece of paper with a message from General McAuliffe.”[i]

“At 0400 on the 26th, the Germans again attacked with tanks supported by artillery and infantry that penetrated the woods held by ‘A’ Company on our left flank. ‘C’ Company in reserve, immediately counterattacked with the help of our 705th TD and drove the enemy back.”[ii]

“Anxious for his wounded, McAuliffe radioed a request that surgeons and medical supplies be flown in by Glider, the only possible way any surgeons could get to the 101st. Apparently, about this time, (perhaps on the suggestion of the division commander, McAuliffe’s G-4), LTC Carl W. Kohls radioed the Air Force to try to get ammunition in by glider, as supplies going in by glider needed no such special packaging as was necessary for a parachute drop. The Air Force had retrieved hundreds of gliders from the Holland operation and had hundreds sitting on French airfields and it remained now to load them and take off.”[iii]

“Back at Bastogne, the battle reached its climax. Another air drop was made over the town, although the response of German flak guns was telling. On the 26th and 27th 962 transports and 61 gliders dropped a massive 850 tons of supplies, with were shot down (sic) and 261 damaged from gunfire.”[iv]

“Five miles south at that moment, 1:30 p.m., Colonel Creighton W. Abrams was standing on a hill looking toward Bastogne. His 37th Tank battalion was the spearhead of the 4th Armored Division driving up from the south to relieve Bastogne. He was scheduled to attack a village several miles to the northwest. But he was down to twenty medium tanks, only enough for one good assault. Should he take a chance and ask permission to blast straight north toward Bastogne? A great roar filled the air. Soon clouds of C-47s flew overhead looking like fat geese. Hundreds of brightly colored parachutes burst over Bastogne. Gliders zoomed toward the ground. Flak burst on all sides; several planes flamed and crashed, but the flights kept coming on. Abrams mind was made up. He returned to his tank, the ‘Thunderbolt IV’, and radioed Hugh Gaffey, Commander of the 4th Armored Division. He asked permission to attack straight north. At 2:00 p.m., Gaffey telephoned Patton. ‘Will you authorize a big risk with Combat Command R for a breakthrough to Bastogne? He asked. ‘I sure as hell will!’ A few minutes after 3:00 p.m., Abrams was handed a message. His face was impassive but his eyes glinted. He shoved a big cigar in his mouth. It stuck out aggressively like another gun. ‘We’re going in to those people now’, he said as he stood up in the turret of his tank. ‘Let ‘er roll.’”[v]

“Then that afternoon the situation took a decisive turn in the Allied favor. At 4:45 p.m. a U.S. engineer on the south of the American perimeter near Assenois excitedly reported the approach of ‘three light tanks, believed friendly.’ Although down to only 20 Shermans, U.S. tankers of Combat Command R of the 4th Armored Division broke through the German ring of the battered 26th Volksgrenadier Division to reach the paratroopers of the 101st Airborne Division. ‘Gee, I’m mighty glad to see you’ exclaimed McAuliffe. The four day siege of Bastogne was over.”[vi]

“The British were ready to lend a hand as well. Lt. Gen. Brian Horrocks British XXX Corps was moving up to ensure that the Germans would find it difficult to cross the Meuse should they reach the river.”[vii]

[i] Glider Infantryman, p. 184

[ii] The Battered Bastards of Bastogne, p. 310

[iii] The Battered Bastards of Bastogne, p. 312

[iv] Battle of the Bulge, p. 201

[v] Battle, pp. 284-5

[vi] Battle of the Bulge, p. 201

[vii] Battle of the Bulge, p. 202

12/27/1944

“But, most important of all, only three miles from the Meuse River and some 60 miles from the starting line, the German spearhead of Hitler’s last great offensive lay shattered and broken in the snow. The Germans would get no further.

Back at Bastogne, the battle would reach its climax[i].”

“…Hitler issued an unalterable decree that ‘Bastogne be cleared’ – a euphemism for the destruction of the American forces in and around the town. The SS Panzer Divisions (or what was left of them) were to be immediately pulled out of the line along with the Fuhrer Begleit Brigade and the 3rd Panzergrenadier Division. These formations were to then be expeditiously moved to the Bastogne salient where they were to ‘lance this boil’.”[ii]

“We went into the barn, so crowded with prisoners that you could hardly turn around. The floor was covered with straw wet with urine and smeared with feces. Anxiously we waited until the enemy soldiers came and took us away several at a time for questioning. …. Additional prisoners kept being added to our number, including the crew of a C-47 that had been shot down on a supply run to Bastogne. The fliers gave us the latest news of the battle, which wasn’t that much, and said Patton’s army had reached the outskirts of Bastogne.”[iii]

“The sun came up bright and clear on 27 December.…The road was open again and more tanks raced into Bastogne followed by supply trucks and infantry that had been waiting in the wings. Replacements would be coming in. We had ammo for all our weapons and food aplenty (both K-Rations and ten-in-ones). Our wounded were being cared for by the surgeons and doctors airlifted in earlier….. We had it made.”[iv]

“Also on December 27 at about Noon, more supplies are dropped on Bastogne from the air through parachutes and gliders. We hear gunfire back toward Marvie as Screaming Eagle patrols attempt to probe enemy positions on Hill 500. Later on that day we hear General Taylor is back in command, and the 101st is getting ready for offensive maneuvers against the enemy.”[v]

“About eight miles from the DZ we started getting small arms fire and something turned loose underneath us. It sounded like large antiaircraft fire. The tow ship then caught fire under the belly and it blazed up suddenly over the whole back end. We flew for about three or four miles further with the blaze getting large all the time. It looked as though the tow ship would blow up any minute. It was burning furiously. Flames were leaping half-way down the tow rope. Just as we got inside the LZ, which would be about four miles from the DZ, two chutes came out through the flames. After about one more mile the third chute came out. About this time, I thought I could make it into the LZ so I released and cut across the LZ, never seeing the fourth chute open.”[vi]

“Nearby, men from the 101st rushed toward the glider and pulled open the door. Brema thought they wanted to see if he was still alive, or perhaps congratulate him for making it without getting killed. Instead, they started pulling and hacking at the lashings, binding the ammunition to the glider floor, and ran off with it, leaving him unceremoniously to his own devices.”[vii]

“An equally important meeting was going on in Germany at the Fuhrer’s daily conference. Von Rundstet was trying to persuade Hitler to abandon ‘Watch On The Rhine’ and retreat before the Montgomery offensive started. ‘I suggest’, he said ‘that Fifth and Sixth Panzer Armies withdraw to a defensive line east of Bastogne’. Hitler was infuriated at the suggestion. ‘Only the offensive will enable us once more to give successful turn to the war in the West. We will renew the drive to the Meuse just as soon as I’ve carried out the next phase of the overall plan – Operation Nordwind….its certain success will automatically bring about the collapse of the threat to the left of the main offensive in the Ardennes’ – he looked around at his commanders – ‘which will then be resumed with a fresh prospect of success.”[viii]

[i] Battle of the Bulge, p. 201

[ii] Battle of the Bulge, p. 209

[iii] Fighting with the Screaming Eagles, p. 200

[iv] Seven Roads to Hell, p. 213

[v] Glider Infantryman, p. 186

[vi] The Battered Bastards of Bastogne, p. 327

[vii] The Battered Bastards of Bastogne, p. 332

[viii] Battle, p. 303

12/28/1944

“The Fuhrer paused. “In the meantime, Model will consolidate his holding and reorganize for a new attempt on the Meuse. And he will make a final powerful assault on Bastogne. Above all, we must have Bastogne.’ By midnight, nine Panzer and volksgrenadier divisions began to converge on the town Hitler wanted at all costs.”[i]

“By now, the Bastogne corridor was broad enough that American ambulances were able to enter the town and evacuate the many wounded, although not without risk from enemy fire. Meanwhile, General William M. Miley’s untried 17th Airborne Division moved up from SHAEF reserve to a back-stop position along the Meuse river south of Givet after coming straight from training in England. Switching places with the 17th, the 11th Armored moved off to Bastogne 24 hours later, ‘on a clear, cold night under an unimaginably bright moon.”[ii]

“Later they took us to a room. Mine was small, the floor straw-covered with blankets. All the other wounded were Germans and I was put between two SS troopers. They did not seem hostile, in fact, it looked like they wanted to talk. However, as I spoke no German and they no English, our conversation amounted to sign language and pidgin English. The man next to me had been an anti-tank gunner and told me about knocking out two American tanks. However, the third got him, killing everyone in his crew but him. He even got a small metal case out of an inner pocket. It contained half-smoked cigarettes and he graciously offered me one. Even though I was never a cigarette smoker, I took a butt and smoked it with him.”[iii]

“It was a misty day. Our fighter-bombers failed to show up but enemy observation planes made runs over the Bastogne sector. There were two small probing attacks in the 401st Glider Infantry area which were quickly repulsed.”[iv]

“Still along the ridge northwest of Marvie, after one road had been opened to Bastogne by tanks of the 4th Armored Division, PFC Charles Kocurek remembers the approach of tanks up the same road along which German parliamentaries had approached on December 22nd.”[v]

“To the south of us, around 0930, I can hear a rumbling over the ridge. The replacements and I look at each other and then back to the south. ‘Could that be some of Patton’s tanks?’ someone mutters. Three US Sherman tanks come into view heading right for us, coming around the curve in the road. Since we are pretty close to the road, I start to get a little nervous. ‘Could be Krauts!’ I say out loud, not really believing the tanks are in German hands. I am concerned about being fired on by the tanks, be they Americans or Germans.”[vi]

“With plenty of ammo now on hand, and more on the way, the gun crews didn’t let their barrels cool. They received their orders and then worked in singing, rhythmic precision – loading and firing, loading and firing again at their distant targets. Loaders would slam the breeches shut and the gunners would hold the lanyards, waiting for the order to fire. ‘Battery, fire!’ a voice would ring out. ‘Now Hitler, count yo’ chillun’ said the gunner each time he pulled the cord, sending death-laden projectiles toward the enemy. Those Negro gun crews were efficient. Hordes of Germans were cut down by the devastating power of their guns. Frozen German bodies lay in almost every wood, field, ditch, and house surrounding Bastogne, bearing mute testimony to the 969th’s deadly efficiency.[vii]

[i] Battle, p. 303

[ii] Battle of the Bulge, p. 212

[iii] FIGHTING WITH THE Screaming Eagles, p. 206

[iv] The Battered Bastards of Bastogne, p. 343

[v] The Battered Bastards of Bastogne, p. 346

[vi] Glider Infantryman, p. 186

[vii] Seven Roads to Hell, p. 214

12/29/1944